Draft Dec 7, 2021

University of Delaware

Water Resources Center

Newark, Del 19711

Introduction

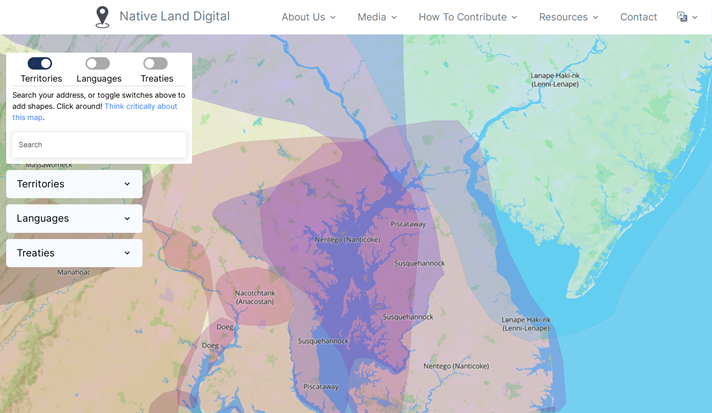

Recognizing the rich Indigenous history and lasting presence of the Native people, the University of Delaware Water Resources Center has dedicated a project aimed at highlighting original place names and their meanings. Indigenous names have always existed for many water-relevant locations, far outdating their anglicized replacements common today. In many places, Swedish and Dutch names established by some of the earliest settlers in Delaware are also relevant to the state’s history, and have been lost in similar fashion. Utilizing 1966 U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1245, the UDWRC mapped original place names of streams and waterways in Delaware (Lenepehocking). Many of the original place names are derived from Lenape, Nanticoke, and Algonkian origin[RH1] reflecting the indigenous people who lived here for millennia. When the Swedes and Dutch sailed here in the early 17th Century, these western Europeans left multiple variants due to differences in spelling and translation among all the influential languages in the area. When King Charles II regained the monarchy after the interregnum of Oliver Cromwell in 1660, the Duke of York granted land charters to William Penn after 1682 and many place names were anglicized and Swapecksiska and Hvitlers Creek became White Clay Creek and the Swedish potato and barley mill snaps Brannvin became the Brandywine River.

The evolution of place names in Delaware mirrors history from the Lenape to the Swedes and Dutch to the English then the Americans. The Lenape lived here for millennia since the melting of the glaciers and the rising of the seas at least 12,000 years ago and met the Europeans in Lenapewihittuck along the river known as Hakenena Sipu (Reed and Wallace 2019). The Europeans arrived at the turn of the 17th Century and met the indigenous people in the tribal homeland of the Lenni-Lenape in Lenape Haki-nk to the north and along the bay, the Nanticoke in Nentego to the south, and the Susquehannock to the west. In 1608, Captain John Smith explored the Chesapeake Bay, interacted with the Nanticoke, and sailed up the rivers of the Eastern Shore into Delaware. The Minqua (Susquehannocks) occupied the west and warred with the Lenape and the Dutch. Peter Lindstrom’s 1654 map of New Sweden identified creeks or kyls along the bay and the Sickoneysincks at Cape Henlopen. Naaman was a Lenape sachem who sought peace with the Swede Governor Printz at a 1644 conference. The Lenape and Minqua fought a trade war from 1626 to 1636. Lenape leadership was through matrilineage where a female matron passed down authority to her heirs and the male sachem was merely a spokesman.

In 1608, Captain John Smith explored the Chesapeake Bay, interacted with the Nanticoke, and sailed up the rivers of the Eastern Shore into Delaware. The Minqua (Susquehannocks) occupied the west and warred with the Lenape and the Dutch. Peter Lindstrom’s 1654 map of New Sweden identified creeks or kyls along the bay and the Sickoneysincks at Cape Henlopen. Naaman was a Lenape sachem who sought peace with the Swede Governor Printz at a 1644 conference. The Lenape and Minqua fought a trade war from 1626 to 1636. Lenape leadership was through matrilineage where a female matron passed down authority to her heirs and the male sachem was merely a spokesman.

In northern Delaware, indigenous villages are found at the Clyde Farm at Churchman’s Marsh, Crane Hook on Delaware River in Wilmington, Naaman’s Creek, and Brandywine River at DuPont Eleutherian Mills at Hagley (Reed and Wallace 2019). The indigenous people named Iron Hill near Newark Marettico, meaning “hill of hard stone” or Aquasehum, meaning “a place where there is iron.” and the Minqua indigenous people had a fort on the hill which was attacked by the Seneca in 1663. Significant to the history of the Brandywine Valley and the Lenape village of Queonemysing is the 1683 agreement between Seketarius and other Lenape sachems and William Penn for the land between the Upland (Chester) and Christina creeks. Queonemysing on the river of the long fish is situated at the bend of the Brandywine just north of the 1682 Penn’s arc of Delaware. Trading stations are found at Frederica on the Murderkill River, Killens Pond, and Saint Jones River near Dover. In 1683 Penn’s William Markham entered into agreement with Sachem Seketarius of Queonemysing and Minguanan (Machaloha) on White Clay Creek. In 1684, Penn identified one mile on either side of Brandywine for Lenape continued seasonal occupation of Queonemysing from mouth to west branch. In 1725, Alphonsus Kirk and Samuel Hollingsworth remembered that land was reserved for Brandywine Indians and the Indians were to retain their “Town on Brandywine.” Kirk remembered: “above thirty years Since he saw two Papers which Saccatarius or some other of the Chiefs of the Indians on Brandywine had in their possession. In 1778, the Lenape (the Delaware) was the first nation (domestic or otherwise) to sign a treaty with the new U.S. government and the Continental Congress.

The Lenape held an annual fish festival on Vandever land on ground now known as Brandywine Village in the spring (Dunlap and Weslager 1960). “Their encampment may be said to have had a general course or range of north west and south east from nearly opposite the present lower dam down to the shipyard and within an average distance of one hundred yards of the creek.” The Indian therefore never failed to indulge his habit in coming down to “fish and turtle” after planting his corn, beans, and other vegetables.

“In the afternoon they would be seen usually returning to their encampment laden down with fish and loggerheads, and upon their arrival would always find a large blazing fire prepared for cooking their fish, the squaws and children having made it up in their absence round a rock or fallen tree. The several groups of returned fishermen would go to their respective campfires, throwing in their fish and placing the great loggerhead in the midst of the coals on his back, keeping him down with stones and watching him preserving the lower shell for a bowl. These festivals generally terminated in five or six weeks, or until they thought their truck should be attended to, when they broke up their camp and returned home.”

The Dutch sailed here in 1616 in search of beaver pelts for the fashionable continental hats of the day and in 1630 founded the colony of Zwaanendael at Hoeren Kill (Whorekill) or Lewes Creek. In 1638, the Swedes founded New Sweden and built Fort Christina (after the teenage queen at the Rocks on the Christinakill) and in 1654 erected Fort Casimir and New Amstel at present-day New Castle. In 1664 King Charles II regained the monarchy after the interregnum of Oliver Cromwell and defeated the Swedes and Dutch here and later the Duke of York granted land charters to William Penn after 1682. By 1700, Penn sold over 800,000 acres of Lenape land in Pennsylvania with more than 9,000 colonists in place. William Penn’s three lower counties of Pennsylvania (New Castle, Kent, and Sussex) were declared under Quaker influence in 1704. In 1767, Mason and Dixon completed the survey of their line that separated the land of the Catholic Calverts in Maryland from the Quaker Penns in Pennsylvania and the land in between was Delaware. In 1776 the Delaware Assembly formed the state of Delaware and separated from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. In 1787, at the Golden Fleece Tavern in Dover, Delaware was the first state to ratify the U.S. Constitution.

Place names of Delaware waterways have fascinating stories. Flowing from Pennsylvania to the Christina River, the Brandywine was called Suspecough the indigenous name meaning, “at the muddy pond” and comes from the Swedish snaps Brannvin a potato liquor after the Old Barley Mill built by a 17th century Swedish surgeon near present day Market Street in Wilmington. The Christina River was the Lenape Sickpeckons Sippunk meaning, “at the river at the muddy pond.” Was named after the teenage Swedish queen. Naamans Creek was named after an indigenous chief around 1655 and may refer to an Algonkian word for fish. Nanticoke comes from the indigenous tribe the tidewater people. Hwiskakimensi Sippus is the Lenape name for Red Clay Creek meaning young tree stream.” Shellpot Creek is the Kitthantemessink from the “large stream at the scattered stones.” Is also from the Swedish Skoldpaddekill or Skillpaddekylen meaning “mud turtle creek.” Sockarockets Ditch flows to the Deep Branch in Sussex County and is thought to have been named for an indigenous Chief Socoroccet who took part in the making of treaties delegating the land in the eastern part of Delaware in the 1680s. The White Clay Creek is anglicized from the indigenous Lenape Swapecksiska which the Dutch adapted to Hwitlerskil.

Indigenous, European, and American Names of Streams and Waterways in Delaware (Lenapehocking) (pdf)